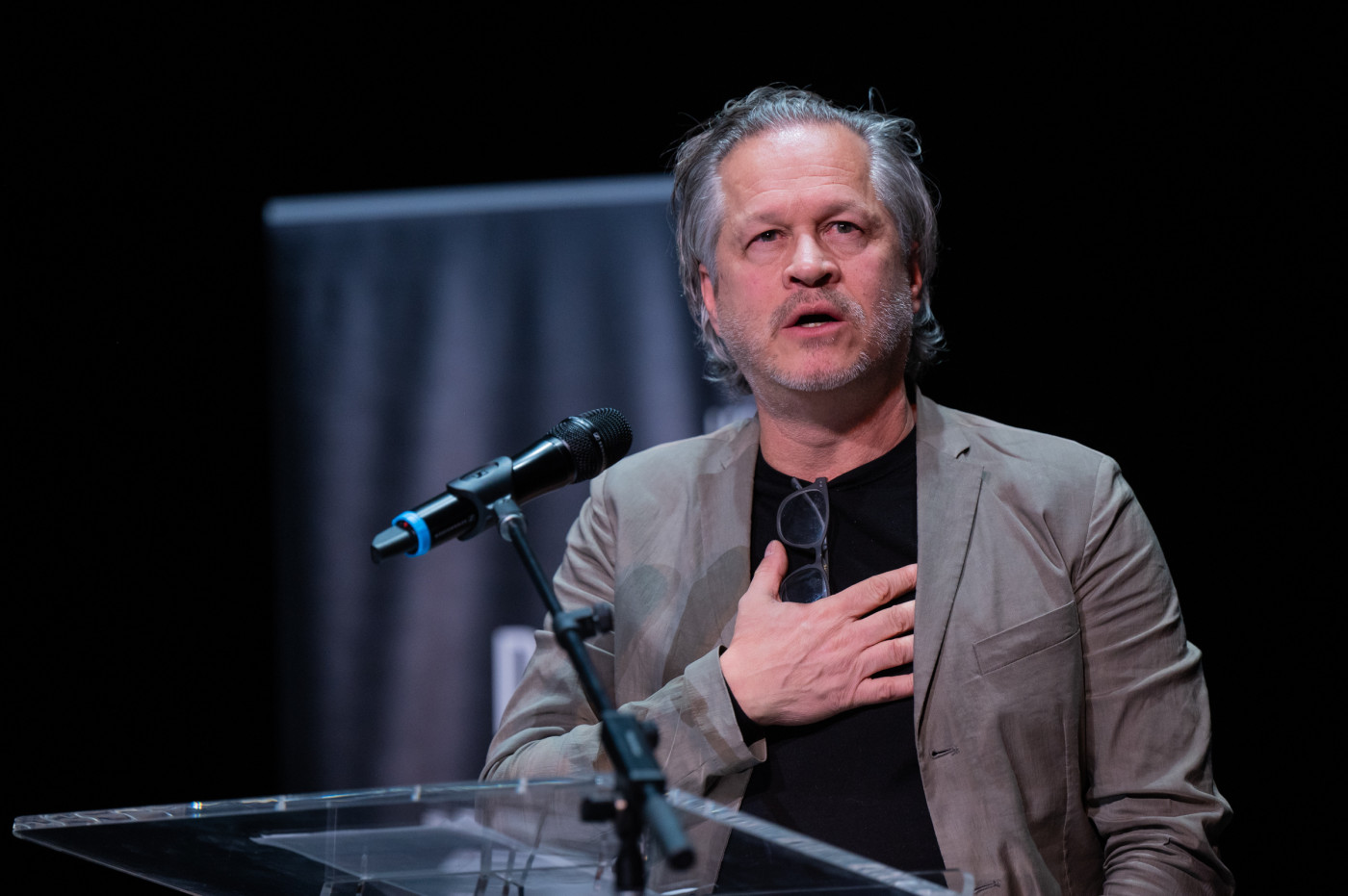

Hofesh Shechter about music, dance and life

Today his Grand Finale is premeiered in Rome for Romaeuropa Fesival

17/10/2018

NdR This interview has been updated. The original version appeared in Danza & Danza International Issue n.5. The Italian version was the cover story of Danza & Danza n.278

A visceral energy inhabits Hofesh Shechter’s dance, almost as though the body were following an innate, impulsive drive towards each movement, with no mediation. The 42 year-old Israeli choreographer, musician and composer is one of the cult names on the British scene and beyond. The best-loved titles from his early career include the dazzling Uprising from 2006, and In Your Rooms from the year after; they revealed his particular appeal, to Italian audiences too after MilanOltre in 2007.

For Shechter, getting groups of musicians involved is standard practice: Political Mother (2010) was hailed as an “audio visual marvel”, while the recent Grand Finale (2017), created for ten dancers and six musicians at La Villette in Paris, drew some 3000 spectators.

Shechter’s career has featured plenty of commissions for external dance companies: the most recent include the rousing Wolf for Aterballetto, and a new version of The Art of Not Looking Back for the Paris Opera Ballet. Other titles have been danced by Shechter II, the youth company whose members change every two years: its new diptych, composed of the revival of Clowns (created for the NDT II) and a new work, will come back to Italy Dec 1 at Teatro Comunale in Vicenza. However, Shechter is coming to Italy before: today his company will premiere at Teatro Olimpico in Rome, for Romaeuropa Festival his acclaimed Grand Finale

Usually, you don’t work using a pre-composed score.

No. I’ve been playing music since I was a child – piano, percussion, I had my own band. Music is central to my work. I go into the studio and I start creating in layers, of musical composition and choreography. I try to find atmospheres, I work with a certain amount of freedom; it’s a very dynamic, elastic process.

In Wolf, the piece you created for Aterballetto, and in other pieces of yours, there’s a dual profile of the group dynamic and the intimacy of the individual. I imagine that this relationship is intended to help the dancers develop a very direct approach to dance.

I never ask the dancers to take off one make-up and replace it with another; and if I’m working with fundamentally classical companies like Aterballetto, I ask them to forget the importance of keeping legs high, of technical virtuosity, to focus on a direct communication of energy, something more related to the imagination, to personal experience, to our more animal, visceral side. The group provides a powerful context for the vision, and, for the audience’s perception too, it’s important to observe the context around the individual. When I come into the studio, if I feel there’s some distance in the group, I move towards the intimacy of the individual; but if that causes me to lose the context, I return to the group: I keep zooming in and out. I did a lot of work on this method in Grand Finale. I’m obsessed with how we work as a group, and as individuals, in a world that’s collapsing. I look at society and what do I see? We try to work in harmony but we collapse, something which is both beautiful and tragic. I don’t know if this can be considered a theme running through all my work; if it’s there, it’s not a conscious decision. However, I am certainly interested in observing society and the individual, but without using a narrative language with characters in my works; what I do is more connected with the surreal world of dreams.

What has stayed with you from the years you spent in Israel, from your childhood, military service?

I think I’m the same person I was when I began studying piano at the age of six. Now I’m a choreographer, I’m well-known, but I must admit that I’m someone who doesn’t trust people easily; I can consciously decide whether or not to believe somebody, but in actual fact I’m very solitary. We could analyse this from a psychological perspective, thinking back to my childhood; I didn’t have a solid family background, but I don’t think that has much to do with it. What counts is the fact that I don’t feel that I belong to anything; it’s a feeling that many people have, and it makes you look at life somewhat from the outside in, as you don’t fully trust others. This means I’m always driven to wonder about the motivations of whoever I’m dealing with. I debate everything, I constantly question whether something is true or not, and perhaps that’s the reason for my attraction to art. Because it’s obvious that in a certain sense, the world of art is fabricated by definition; just think of dancers, for a show they put on costumes, makeup, then there are the lights, the scenery, it’s all fictitious, but it’s so overt that that fictitiousness in itself lets you go beyond it and explore reality. So, just like when I used to play music as a boy, when I listen to music, when I play it, when I dance, I feel no separation between myself and reality, between the truth and myself, it goes deeper than any verbal exchange, or any objective exchange in my life with people, with my family, my teachers, my friends. In art, I find an essence which I feel in nothing else.

As for military service in Israel, it was quite a shock for me; having been brought up in a democratic society, at the age of eighteen I found myself in a hierarchical, extremist organization. As though there were one country inside another. I was already a dancer, so my service wasn’t that hard; I alternated my work in the dance company with a job in a military office; some of my peers had a much tougher time, they spent the whole day running, or practicing using weapons. Yet it was a harsh experience. I saw it as a sort of segregation, during which everything was meant to be channelled towards peace, but then the sensation you feel is something else; it’s like when you see a spider and your first instinct is to kill it to save yourself. I could see the fear, the collective hysteria. In itself, the organisation is an excellent thing, but how should we put it to use? It was a confusing experience for me, and left me with a need to think about how our society works.

The relationship between organisation and freedom is also central to your approach to choreography… Indeed. I’m always in conflict with choreography. I’m searching for freedom through dance, but then we must organise that freedom into a choreography which isn’t written in stone, and then grasp how much that choreography belongs to us, as choreographers. When it’s there, I’m not there; in the performance it belongs to the dancers, to the stage. Yet choreography means making decisions, saying yes and no; but is freedom everywhere, or where I decide it is? There’s something philosophically unfathomable in that.

© Riproduzione riservata